My starting place is Ariadne, of course. But that’s not what this post is about. This is an exploration of some stories that gather to the constellation Corona Borealis besides the ones of Ariadne and Dionysus. But I’ll start where I must always start.

For me, Alphecca is as quiet as sleep and as loud as the carnival she brings with her. She reaches for you like ivy. Spindle-spinner, grape-treader, trance-inducer, maenad-stirrer, The Mistress of the Labyrinth requires her share of honey. She is rose-colored glasses you have no reason to take off. She is a dance floor, a parade, a hall of mirrors, a misty garden, a hedge maze. In her world, I am seduced, I am giddy and in love, I am mesmerized and nothing is quite as it seems, and I never want to leave. She is forgetting what is ugly and unkind, and remembering only what is feels good, smells good, tastes good, what is easeful, pleasurable, delighting.

For the Romans (who would later outlaw their cults), Ariadne and Dionysus were Libera and Liber. They are freedom from worry, from anxiety, from labor. Such freedom is inherently social and these two are social. She and Dionysos are so often portrayed in their noisy procession or seated upon their couch, surrounded by maenads, satyrs, nymphs, and erotes. They lead but they are a crowd.

But this post attends to other tales. The outline of this post is:

Nanaya, Goddess of Love

Snake Gods (The Sitting Gods)

[Redacted section; please see note]

Arianrhod

Ariadne (A Short Preview)

I have plans for more, of course. More on Ariadne. A post about Alphecca’s plants: ivy and rosemary. If you follow me on Instagram, you might have seen me put a call out for volunteers with Alphecca in their charts. Thank you to everyone who said they’d chat with me. I’ll be reaching out to you later this month. Lots to share. Lots coming.

This first post, however, is pretty research-focused but still it’s very personal to me. This May, I wrapped up a 12th house profection year ruled by the Sun and my Sun is in paran with Alphecca. In that year, she became even more palpable. I saw more clearly how she is always in the 12th with me, placing soft sweet-smelling violet paste on my eyelids, easing me into her dreamworld, or handing me a cordial that brightens my heart when I feel totally rearranged and unknown to myself.

Alphecca is lubricant on the camera lens, softening the focus. She is a drumbeat in my ears that I realize is my own blood. She is in my ankles that want to remember this body used to dance. She is pale purple-pink flowers and gloaming blue and shimmering stars. She is a gleaming feast and the eagerness and joy in everyone around its table. It is her.

This writing is for you but it is also for her. It is an offering. The first offering was a podcast episode of Radical Elphame (give it a listen if you haven’t!) in which I shared a bit about my understanding of Ariadne and Dionysus. This post is the public second offering to Alphecca, of who can say how many.

As you read this piece of it, know that even if you don’t have Alphecca in your chart by paran or conjunction, you can still develop a relationship with this star if you’d like. Know also that the stars in your chart are this densely populated with images and stories too. This is why I love the fixed stars so very much.

(If you aren’t sure how to tell if a star is in your chart, see if you have any traditional planets, nodes, lots, or angles within 3° of Alphecca’s projected degree, approximately 12° of Scorpio. To check parans, follow the instructions Amaya Rourke posted here.)

If you’d like to get to know the stars in your chart, let’s talk about them. I’m traveling this month so my availability for September was limited and is already full, but I released my October calendar already. I’m eager to introduce more people to the fixed stars and to have in-depth conversations with those already familiar.

corona borealis

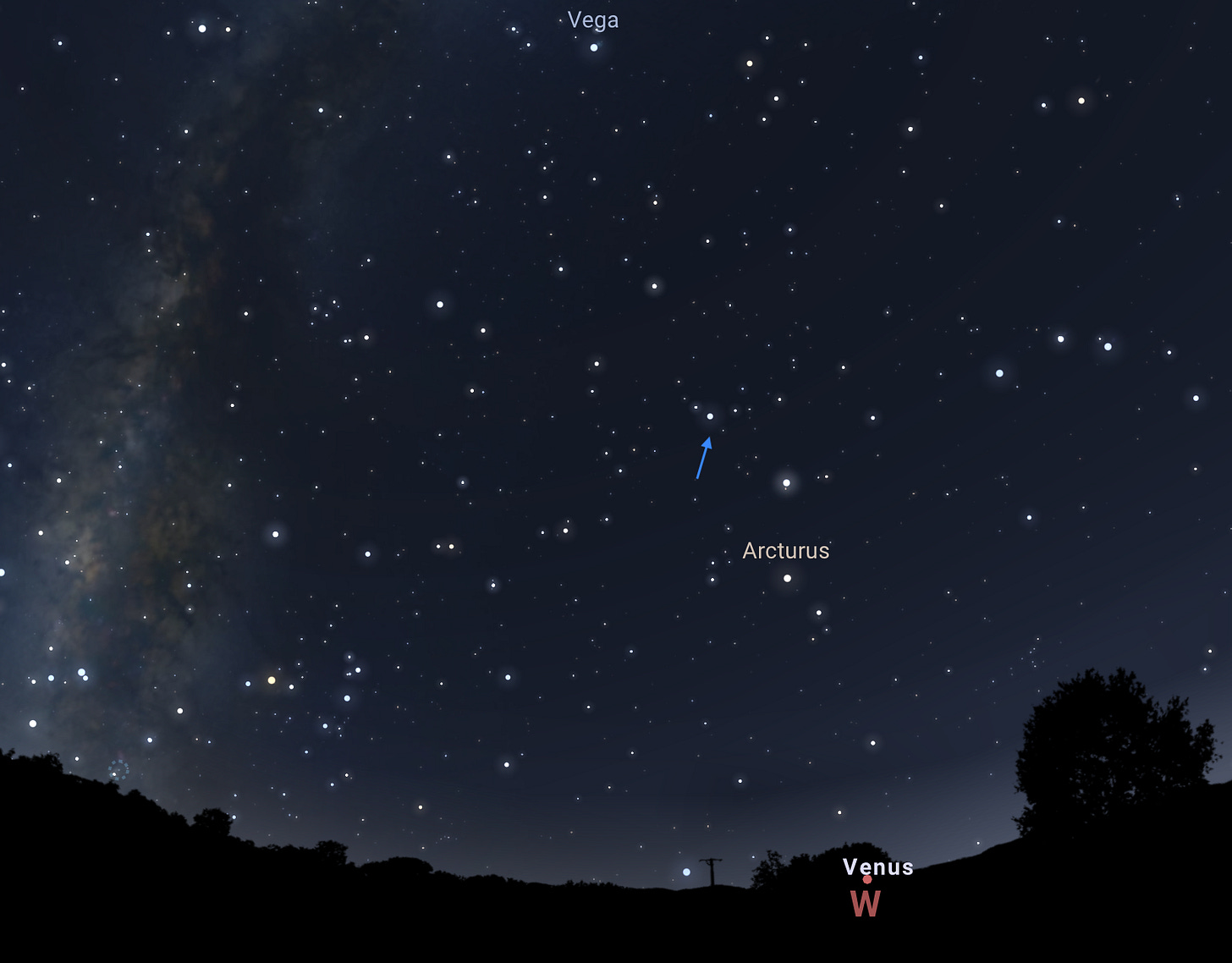

Corona Borealis is one name for a semicircle constellation made of 7 distinct stars. Corona Borealis sits between Bootes, Heracles, and Ophiuchus’s snake’s head. Corona Borealis is a small constellation and not particularly bright. If you can find the star Arcturus, look to the upperleft (in the Northern Hemisphere) and you’ll probably see Corona Borealis’s brightest gem, the blue-white Alphecca.

The stars in Corona Borealis are 4th-magntitude stars except for Alphecca which shines at an apparent magnitude of 2.23 (for comparison, Arcturus is -0.5 apparent magnitude and Alkaid is 1.84, and the smaller the number, the brighter the star). Despite being small and somewhat faint, this constellation is storied and admired in many cultures for its beauty.

Corona Borealis translates to “northern crown” in Latin. It was called “Stephanos” meaning “wreath, crown” until it needed to be distinguished from Corona Australis, the southern crown. While I associate crowns with kings and queens, “stefanos” refers to the crowning of all sorts of people as a reward or honor. Think of the laurel wreaths on writers, scholars, and winning athletes. Think of the way people wreath and garland animals to honor them, to protect them, to celebrate them and the seasons, how we wreath and garland locations to make them festive. Think of the floral wreaths on the heads of May queens, and on the heads of brides and grooms.

nanaya

According to the MUL.APIN, a compendium of Babylonian star catalogues probably compiled around 1000 BCE, Corona Borealis is sacred to a love goddess called Nanaya (also called “Nanay” or “Nanāia”). One of her epithets is bēlet ru'āmi, “the lady of love” (Drewnowska-Rymarz, 2008). Her other repeated descriptors are ḫili in Sumerian and kuzbu in Akkadian. These words can be translated as “charm,” “luxuriance,” “voluptuousness,”“sensuality,” or “sexual attractiveness.”

Based on poetry, hymns, spells, and the location of her temples, scholars often depict Nanaya as a face of other, more famous goddesses like Inanna, Ishtar, and Isis. Magic done with Nanaya as a patron included all sorts of incantations of erotic, romantic love, perhaps most popularly asking that love be returned. Nanaya is connected to kings and rulers as well, particularly with regard to something like hieros gamos (the spiritual marriage between the ruler and a goddess as legitimation of rulership) (Holm, 2021; Asher-Greve and Westenholz, 2013).

Of the goddesses I listed above, Nanaya’s relationship to Inanna is particularly strong. Nanaya is sometimes described as Inanna’s alter ego or daughter or as Inanna herself, as if when Inanna simplifies her many attributes down to being only her lover aspect and/or her “celestial” aspect, she goes by “Nanaya” (Schumann and Sazonov, 2022; Holm, 2021; Steinkeller, 2013; Asher-Greve and Westenholz, 2013).

There is good reason, however, to honor Nanaya as her own separate entity (Schumann and Sazonov, 2022; Holm, 2021) even while she is enmeshed with these other goddesses who are more well-known to us. I don’t want to put spirits into tidy boxes but I also don’t want to repeat all too common pattern of smushing all goddesses into one “great mother goddess.” Both moves do a disservice to the spirit in question.

Nanaya was famous of her own accord, for a long time and all over the world. She was worshiped across Babylonia, into Assyria, from Egypt to Persia (where she was called Nana), and into India and China (Schumann and Sazonov, 2022; Holm, 2021; Asher-Greve and Westenholz, 2013). At times, she may have even (I shudder to say it) exceeded the worship of Ishtar. In 1997, Joan Goodnick Westenholz wrote, Nanaya

appears from nowhere to become the greatest Mesopotamian goddess of all times – greater than the Sumerian Ninḫursaĝ, the highest lady of the Sumerian pantheon, more enduring than even the Semitic goddess par excellence, Ištar.

All I’m trying to say is Nanaya is a big deal.

I want to share a song of praise to Nanaya now. It is described as a song of praise for Inanna roleplaying as Nanaya. To which I shrug. Regardless, I just gave you a lot of citations and quotes from scholarship, and that can be pretty stale compared to what actually brings Nanaya into the room. This passage, even fragmented, maybe even better for being fragmented, is more effective than any collection of academic thought for understanding who Nanaya is. Enjoy.

“Let me… on your… — Nanaya, its… is good. Let me… on your breast — Nanaya, its… flour is sweet. Let me put… on your navel — Nanaya… Come with me, my lady, come with me, come with me from the entrance to the shrine. May… for you.. Do not dig a canal, let me be your canal. Do not plough a field, let me be your field. Farmer, do not search for a wet place, my precious sweet, let this be your wet place…, let this be your furrow… let this be your desire! Caring for… I come… I come… with bread and wine.”

Nanaya is charming, joyful, loving, and explicitly erotic. Her worship is too. That Corona Borealis is her constellation tells us a lot about how we think about those stars. In this passage, Nanaya is associated with putting aside the toil of agriculture for the pleasures of the bedroom (or wherever).

Because Ariadne and Dionysus are my entryways to this part of the sky, when I read “Farmer, do not search for a wet place… let this be your wet place,” I also hear the putting down of labors associated with the lady of labyrinth and her consort. I see Ariadne on her couch, smiling, drifting in and out of dreams in the warm air, absently petting a leopard — seduction a perfume around her. Nanaya was invoked at weddings and particularly for wedding nights. Ariadne is most famous as bride. Her crown is a bridal crown.

Nanaya and Ariadne are not the same being but it is not hard for me to feel for why they could like the same set of stars in the sky.